Finding the stories behind the statistics

Reporting on the 1,200 American kids killed by guns since Parkland

Chances are, you care about gun violence prevention. You remember Parkland. You remember March For Our Lives. Maybe you participated in Mason’s walkout last year, or follow Emma Gonzalez on Twitter. As a largely liberal and politically conscious group of young people, gun reform is a priority for George Mason students.

I am no different. I was inspired by the mobilization our generation experienced following Parkland. I have been to the marches. I want change. But until a few months ago, I could probably name more gun control activists than gun violence victims.

In Falls Church, a city unfamiliar with everyday gun violence, you’re probably only aware of the nationally covered mass-shootings. You’ve seen the CNN specials and hashtags. But you haven’t heard the devastating stories of everyday gun violence- domestic incidents, accidental shootings, gang violence, and drive-by shootings.

While we as a community may care about the gun violence epidemic, how many of us know the stories behind the statistics? With so many deaths, the victims of America’s distinctive crisis become nameless. Since Parkland, a student journalism project organized by the Miami Herald and The Trace, aims to change that.

For six months, I worked with 200 other student writers on Since Parkland, memorializing the 1,200 American children and teens fatally shot in the year after Parkland. I was assigned 23 names and was asked to write about what made each victim unique.

As five of my peers note in an introduction to the project, “Our goal is to shift the attention away from the numbness that seeps into the discussion around gun violence.” In creating Since Parkland, our goal isn’t to politically inspire you, they explain. “We want to overwhelm you,” because gun violence is overwhelming before it is politically inspiring.

The experience of writing for the project was overwhelming. Learning their stories had me crying into my laptop, sick to my stomach.

I wrote about Kaleigh Pennington, a 10-year-old girl accidentally shot by her twin brother when he found a gun beneath the seat of their family’s truck. I wrote about Natalie Gulizia, a 14-year-old girl who came home to find her little brother in zip ties, her mother holding a gun – she was shot in the head while she was calling 911. I wrote about Benjamin Workman-Greco, a 17-year-old boy who was shot in his own apartment and died in his fiance’s arms.

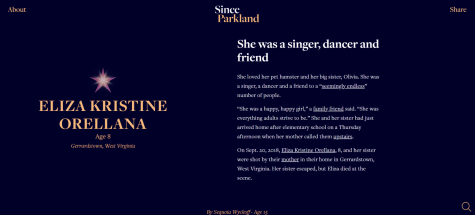

Eliza Orellana loved her pet hamster and her older sister, Olivia. She and her sister had just arrived home after elementary school on a Thursday afternoon when they were called upstairs. On Sept. 20, 2018, the eight-year-old was shot by her mother in her West Virginia home. Her sister escaped, but Eliza died at the scene.

Sateria Fleming’s friends called her by her nickname, Zoe. “So bright, so beautiful, so blunt, so Ms. Sassy,” a classmate described her. She was full of energy and encouragement. She was 16, and on March 26, 2018, she was shot in the street in Greensboro, North Carolina.

Zaniyah Burns was in second grade, and she loved it so much she wanted to be a teacher. Her grandma called her “Banana Pudding.” Other family members called her “Toot Toot.” As she was getting ready to take a bath, two gunshots flew through the window. She was shot in the head in her home in Flint, Michigan, on Oct. 9, 2018. She was seven years old.

It wasn’t only the tragedy I encountered that was overwhelming – so was the underreporting and misreporting I had to sift through as research. For the most part, these victims didn’t make headlines. Instead, they made two-minute segments on the local news and a page on an obituary website.

I couldn’t even find the name of a two-year-old boy in Alabama who reached for a gun on his kitchen counter and shot himself in the head. It is heartbreaking that after weeks and weeks of research, I found nothing more than an age and date of death, as well as a haunting reminder of the ubiquity of gun violence in America. (See: Stories Left to Tell)

In local news stories, there were inconsistencies and errors. It’s upsetting to see a news site incorrectly report the name of a dead child. One of my peers, Taniayah Dorsett, wrote a story for Since Parkland highlighting this misreporting: “The Clarion-Ledger called him Dementric. NBC/ABC affiliate WDAM 7 used Delametric in a story and Delmetric for a photo caption. The Gun Violence Archive listed him as Dementric. According to his family and Facebook, his name was Delametric Djaun Fairley.”

Reading the stories we have written might take all you have in you. That’s the point. There are 1,200 dead children who deserve meticulous reporting, which may be hard for readers to stomach.

Gun violence is gutting, it is sickening, it is devastating. And yes, it is political, but only after we take the time to absorb its horrors. Let the stories we’ve told inspire action – but first, let them overwhelm you.