This is what quality journalism looks like

Measuring–and fighting–prior restraint’s effect on student journalism

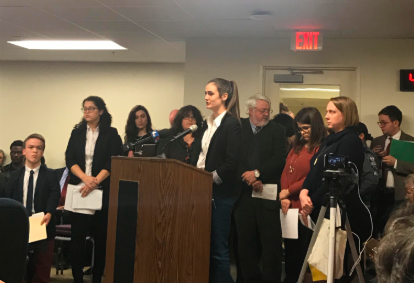

Kate Karstens testifies in front of the Virginia House Subcommittee Education Subcommittee 1. Over 40 students, teachers, and principles–former and current–arrived to testify in support of New Voices legislation. However, only four were allowed to testify by the Committee Chair, matching the number who came to oppose the legislation.

For almost 30 years, Mike Hiestand has been asking the same question to student journalists who call his legal hotline.

“‘Where are you calling from?’”

“The answer to that question will very likely determine whether or not the information I’m able to provide will get them out of their problem or not,” said Hiestand, an attorney, and activist who currently serves as the Senior Legal Counsel to the Student Press Law Center (SPLC).

“It really does make all the difference.”

Hiestand, who has close to 30 years of experience in scholastic press law, spends much of his time helping student journalists overcome administrative censorship. In 14 states, the legal strategy is simple. Invoke a “New Voices” law, which provides explicit protections against prior review and restraint.

However, in 36 states including Virginia, press freedom advocates lack clear legal recourse when administrators block content deemed inappropriate or disruptive.

“It’s a humiliating feeling to have your work taken down and then be told ‘this isn’t really what our community is about,’” said Kate Karstens, the former Editor-in-Chief of the Lasso, who now writes for the Tar Heel at the University of North Carolina.

During her time as a student journalist at both GMHS and UNC, Karstens experienced censorship on several occasions.

“One article was about how students were abusing the absence policy. A student told me how many absences he had, and told me ‘you can publish this.’ The school censored the article, and initially, I didn’t even get a reason.”

In another incident, the Lasso attempted to publish a photo of vandalism in the school bathrooms, which administrators also blocked, according to Karstens.

“[They] took the article down because it could ‘disturb what’s going on in school right now’ but they didn’t get that the vandalism is what’s ‘disturbing school right now,’” Karstens said.

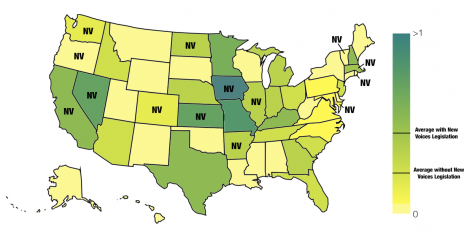

The Lasso compiled data from student newspapers in all 50 states to assess whether or not protections under New Voices laws have a positive impact on the quality of journalism. We found that there is a significant difference between the number of awards won per school in states with and without New Voices. This reaffirms the observations of Hiestand and other student press advocates.

Awards per school in each state

“Anecdotally, it seems like the states with these New Voices laws are the ones winning big awards like Pacemakers [for student journalism],” said Hiestand. “It does make sense because if students want to do more hard-hitting journalism, it’s not something that school officials would be able to shut down.”

Karsten’s experience is commonplace for student journalists and editors working in prior restraint states like Virginia. Take, for example, these incidents in the last three years:

In Texas, a principal banned students from publishing “controversial stories,” including about a book with gay characters and another addressing walkout protests. In Utah, Herriman High School administrators took down the website of students journalists reporting on a missing teacher. And an hour away from George Mason, Fauquier High School Principal, Clarence Burton, censored student journalists working an investigative piece about marijuana use.

But why do First Amendment protections only apply to students in specific states? The answer lies in half a century of Supreme Court precedent.

In Tinker v. Des Moines (1969), Supreme Court Justices affirmed student’s protections under the First Amendment, namely, the right to freedom of expression on school grounds. In effect, a student in an American public school has the right to espouse any political or moral viewpoint, as long as they do not engage in “substantial disorder” or the “invasion of the rights of others.”

These protections were so strong, they prompted the creation of the Student Press Law Center, a non-profit entirely dedicated to defending the rights of student journalists.

“We came onto the scene right after the Tinker case was handed down,” Hiestand said. “It provided very significant protection to student expression.”

However, these broad protections were crippled in 1988, in Hazelwood School District v. Kuhlmeier, when the Court ruled that the First Amendment does not apply to student press freedoms.

According to the Supreme Court, student newspapers are not inherently public forums like their professional counterparts and instead serve as supervised learning activities, subject to censorship by administrators.

“If all school officials have to do is show that an article is poorly written, or inappropriate, or inconsistent with social values,” said Hiestand, “it’s a huge frustration on my part as a lawyer because we can’t take those cases to the court of law.”

As a result, after 1988, the SPLC “decided that the First Amendment was no longer the place where most students would be able to go for the most protection.” Instead, the organization looked towards a once-obscure law in California for guidance.

In 1977, the state codified the legal standard of Tinker, an unlikely decision considering Supreme Court precedent at the time protected student journalists from censorship. After the Hazelwood ruling, however, the law became the gold standard for student press freedom across the country.

As Hiestand puts it, “the government can never pass a law that provides less protection for the First Amendment at the state level, but it can always pass a law that provides more.”

Through a prolonged campaign of lobbying and advocacy, the SPLC helped 13 more states successfully pass “New Voices” legislation. This January, they attempted to do the same in Virginia.

Sponsored by Delegate Chris Hurst, a former journalist from Montgomery, House Bill 2382 would have guaranteed freedom of speech and the press to student journalists. However, the proposal was quite controversial, with supporters and opponents of the bill packing the room. Eventually, the bill failed in a tie vote.

The Lasso reached out to Thomas Smith, the legislative liaison for the Virginia Association of School Superintendents, a group that publicly opposes New Voices legislation. He did not respond to requests for comment. However, in the public hearing on HB 2382, he argued against press freedom for students, citing age differences:

“We’re not talking about an 18- or a 19-year-old; we’re talking about possibly a 14- or 15-year-old writing a story.”

Virginia, along with New York, has one of the most disappointing records of journalistic achievement given its population size. However, advocates for reform have not given up hope.

“The bill was a tie so it didn’t make it onto the floor,” said Karstens, but “we will try it again in 2020.”

While the second attempt may be more successful, the fact remains that for many students across the state and country, first amendment rights are severely curtailed.

And as a result, the first question Hiestand asks students who call his legal hotline will continue to be: “where are you calling from?”

Colter Adams is the Lasso's Senior Political Junkie, and Managing Editor. He is also a part-time musician and a massive film buff.