A case study of partisan gerrymandering; it’s corrupt, but is it unconstitutional?

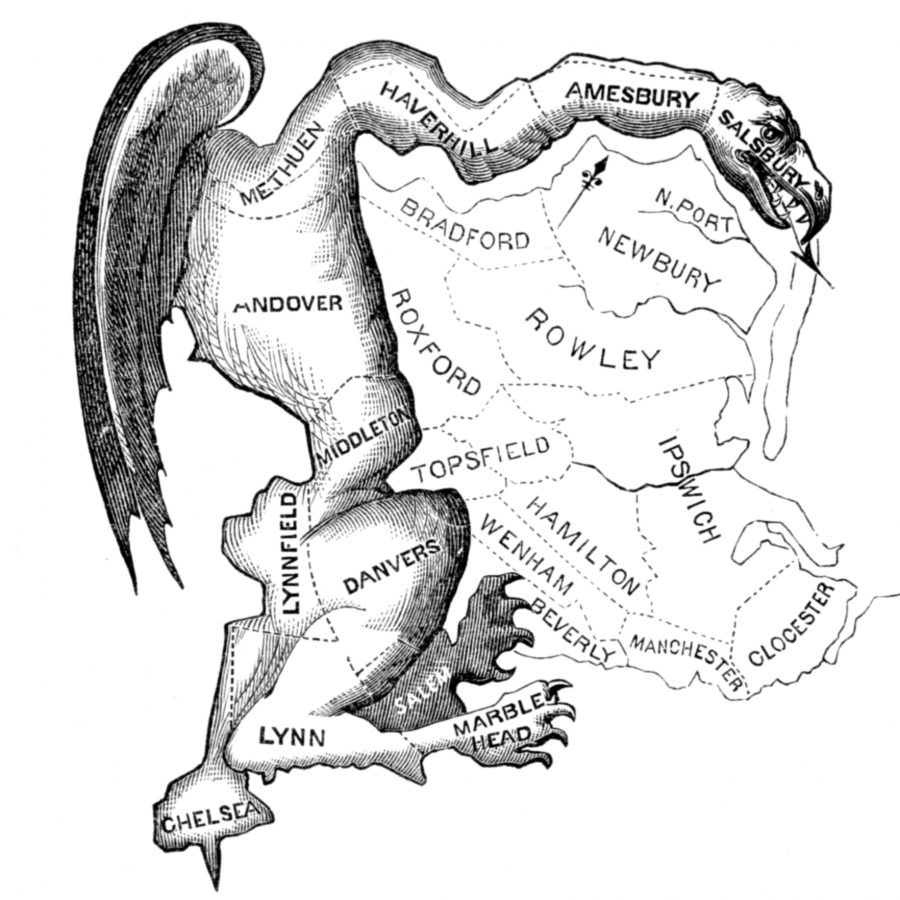

A political cartoon published in March 1912 to mock the unusal shape of Massachussetts district Essex County. (Photo Courtesy of Wikipedia)

November 15, 2017

The Supreme Court will soon be deciding once and for all whether the Federal Government will (or can) prevent the form of partisan election rigging known as gerrymandering.

Justices are currently hearing arguments for case in question, Gill v. Whitford, and are expected to come to a resolution in the coming weeks. The result of the case will have wide-ranging impacts. A decision negating the constitutionality of partisan gerrymandering would result in the largest redistricting challenge our nation has ever faced, including in our very own heavily gerrymandered state. On the flip-side, a decision in support of its legality would strike down several anti-gerrymandering measures passed by state governments across the country, such as in Ohio and Pennsylvania.

But before addressing the case in detail, it is important to overview what gerrymandering is, as well as why the federal government’s prospective role in ending it is still cause for debate.

Gerrymandering is essentially the process of influencing elections in favor of one party by redrawing electoral district boundaries.

While it may seem like only those who directly benefit from gerrymandering would dare to promote it, before we uniformly advocate against the process, it is important to understand how the defense of gerrymandering is devised.

Afterall, most opponents of reform agree that gerrymandering is often used to rig districts in favor of the majority party.

GOP official Dennis Gasper, part of a team defending the state of Wisconsin’s redistricting procedures, has acknowledged this publicly.

“[Are] the Republicans in the legislature going to set this thing up so Democrats can win the legislature? I wouldn’t. Sometimes it works for the Democrats, sometimes it works for the Republicans.”

While this may seem like a questionable response to accusations of unfairness, this is because the question it is often inaccurately framed. It is not whether or not gerrymandering is ethical; it is whether or not it is constitutional. A Supreme Court intervention on the issue would take away a power that has been delegated to the states for the entirety of our existence as a nation; the reserved power to draw their own electoral maps.

However, expressed constitutional rights supercede the reserved powers of the states, which is why certain types of gerrymandering have already been ruled unconstitutional in the Supreme Court case Shaw v. Reno (1993) based on the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment which states, “no state shall deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.”

Despite this, an instance of gerrymandering must reach an extremely high burden of proof in order to be struck down by the 1993 court case, one which is must higher than most current examples meet.

According to the ruling “[a] threshold showing of discriminatory vote dilution is required for a prima facie case of an equal protection violation.” This means that in order for a case of gerrymandering to be considered unconstitutional, it has to be based on non-political factors such as race or religion.

Without an additional Amendment, determining a constitutional basis for ending partisanly motivated gerrymandering uniformly would be a very big step.

After all, the 10th Amendment to the Constitution states that “any powers that are not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, are reserved to the states respectively, or to the people,” and the ability to facilitate the drawing of state electoral boundaries is neither an enumerated or implied power of the federal government.

Another problem with ending partisan gerrymandering is that there is not an easy alternative to replace it with. While it is true that many state legislatures are rigged in favor of one party, gerrymandering is used by both parties to draw district lines; the Democrats in states like Maryland and Illinois, and the Republicans, well, most everywhere else.

Both minority and majority parties in state legislatures tend to support gerrymandering because not only is it a systematic way to determine which seats should be allocated to which geographic areas, but it protects minority party seat holders as well by guaranteeing that the districts they do hold are easy victories.

This is largely a strain on the Democratic process, considering it reduces the competitiveness of elections and by extension the obligation of representatives to appease their constituents, considering most voters vote purely on partisan lines. Gerrymandering could be considered a major reason that politics have become increasingly polarized, as no representatives are obligated to compromise because they represent such overwhelmingly liberal or conservative districts.

This occurs at the national level too. The political polling website FiveThirtyEight estimates that since 1992, the roughly 103 members of the House of Representatives elected from what might be called swing districts, has dwindled to around 35.

Unfortunately, because most policy makers are benefited personally by gerrymandering, we cannot rely on our elected representatives to pass legislation in favor of non-partisan redistricting.

Thus this puts us in the precarious position of asking for help from the only branch of government that does not have an obviously plausible basis for legally ending gerrymandering; the judicial branch.

So could there be a Constitutional basis for an end to gerrymandering? And if so could it be properly and realistically administered?

Fair representation advocates do have a secret weapon in the form of a Supreme Court which has become increasingly sympathetic and receptive, if continuously ineffectual, regarding anti-gerrymandering arguments.

In 2004, the Supreme Court struck down an argument regarding the unconstitutionality of gerrymandering, but by a very close margin. And the tie breaking vote was a reluctant one.

“It is unfortunate that our legislatures have reached the point of declaring that when it comes to apportionment, we are in the business of rigging elections,” wrote Justice Anthony Kennedy in his concurring opinion, after voting against judicial action. “Still the court’s own responsibilities require that we refrain from intervention in this instance.”

However Kennedy indicated that his position could change, “if workable standards do emerge to measure these burdens [of partisan gerrymandering].”

And now he may get that chance, which brings us back to Gill v. Whitford.

Five justices so far (including Kennedy), have been extremely critical of partisan gerrymandering during the early weeks of the case.

Sonia Sotomayor, of the reliably liberal contingent of the Court, was the most openly disparaging. “Could you tell me what the value is to democracy from political gerrymandering? How does that help our system of government?” Sotomayor asked attorneys defending partisan redistricting in the state of Wisconsin.

Justices have also been presented with a relatively new constitutional argument against political gerrymandering in Gill v. Whitford; that it violates the 1st amendment right of freedom of association for members of a minority party. In other words, partisan redistricting overseen by a majority party reduces the impact of the votes of minority party supporters. By extension, this results in reduced representation for members of a minority party, purely based on their choice of how to assemble.

Coupled with a definitive and encompassing method of determining where gerrymandering is taking place, this argument could potentially provide the constitutional basis that previous arguments against gerrymandering have lacked, which is why the coming Supreme Court decision is one to pay close attention to.