The truth about College Board

The company behind the SAT has a history of racism, greed, and inequity

It’s that time of year again.

As a junior, I can’t spend more than five minutes in the hallway without hearing my friends anxiously comparing PSAT results, and debating what constitutes a “good score,” or what qualifies for “National Merit Scholarship.”

Eventually, they get tired of comparing their own scores, and someone asks: “How’d you do?” They don’t need to clarify what they are talking about. It’s obvious. I’ll hear the question dozens of times the day scores are released.

If you attend a public high school, chances are you have come across at least one product offered by the College Board, an organization with the purported mission of “promoting equity and excellence in education.”

These products play a significant role in the college application process for high school students, particularly the AP courses.

“Colleges have historically used the rigor on transcripts to make admissions decisions, and the advanced academic programs in most high schools are based on College Board classes,” said Daniel Coast, the IB Diploma Coordinator at George Mason.

While the tests themselves do have value, the organization that administers them possesses a dangerous and damaging monopoly on the public education system.

George Mason High School relies on both curriculum and tests offered or sold by the College Board. The company is responsible for designing the curriculum and administering the tests for the six AP courses taught at Mason. In addition, the College Board provides the SAT, and PSAT, the latter of which George Mason pays for all students to take.

And while, according to GM counselor Ms. Valerie Chesley, the PSAT is “optional” for students, many informed the Lasso that they were told, or believed, that they were required to take the PSAT.

“I didn’t know I could opt-out,” said junior, Miles Hefferan. “[I] probably would have as a freshman or sophomore if I knew.”

Independent of this lack of clarity, one thing is certain: the College Board is deeply ingrained in the college application process and academic experience at George Mason High School. This means that students must invest a great deal of trust in the organization’s motives and objectivity.

But has it truly earned this trust?

The first Scholastic Aptitude Test (SAT) that the College Board ever administered was designed in 1926, by Carl Brigham, a psychologist who believed his test would confirm the superiority of the “Nordic race.”

A notable eugenist, Brigham suggested that “American Negroes, the Italians, and the Jews were genetically ineducable,” and claimed, “it would be a waste of good money even to attempt to try to give these born morons and imbeciles a good Anglo-Saxon education.”

While Brigham eventually renounced his beliefs, many watchdog groups argue that the test he created now sustains a system of racial discrimination within the education system.

According to a National Center for Fair and Open Testing study, “on average, students of color score lower on college admissions tests,” and as a result, “many capable youth are denied entrance or access to so-called ‘merit’ scholarships, contributing to the huge racial gap in college enrollments and completion.”

The study also concluded that such tests are “often inaccurate for English Language Learners, leading to misplacement or retention.”

While these problems are not exclusive to SAT and AP tests, in recent years, the College Board has achieved particular notoriety for turning a system of student disenfranchisement into a thriving business model.

In 1995, the College Board hired Gaston Caperton, a former governor of West Virginia, to address cash-flow problems. Caperton quickly set about transforming the non-profit into a highly profitable endeavor, hiking prices to take tests, and buying a large share of the test preparation industry.

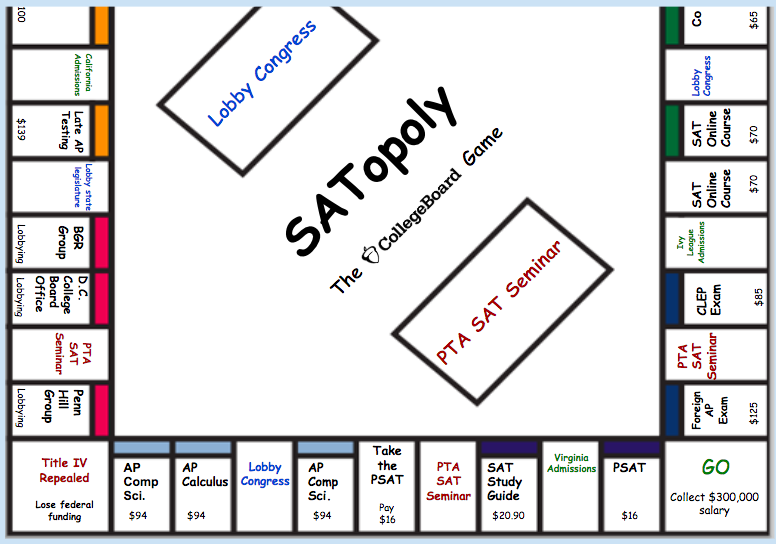

As a result, the College Board’s profits skyrocketed to about 60 million dollars a year — 317% above the industry average. Additionally, the salaries of executive board members increased to over $300,000 a year and it’s president, David Coleman, earned $550,000, with a total compensation of $750,000.

The College Board’s new sources of revenue have done more than simply enrich its administrators.

Since 1995, the organization has spent over $4.7 million on lobbying efforts, using its massive warchest to further latch on to the public education system. According to The Hechinger Report, in California, the organization attempted to make AP classes mandatory in every high school, and in Indiana, lobbyists pushed for a bill to allocate $500,000 for ACT/SAT test preparation.

At the national level, the College Board employs seven registered lobbyists from three separate firms and has successfully pushed legislation to increase federal funding for AP tests through Congress.

The non-profit’s transformation from a flawed educational advocacy group to a thriving commercial enterprise has not gone unnoticed.

A lawsuit was filed against the College Board in Illinois for selling test-takers’ information to colleges without their consent — a practice which accounts for a significant amount of the non-profit’s revenue. This includes the personal information students fill out before taking the PSAT, SAT, or an AP exam, such as “race/ethnic group,” “grade-point average,” and “mobile phone number”; none of which is indicated to be optional.

The College Board has also come under fire from student groups for charging families $25- plus $16 per college- to use a tool called the College Scholarship Service (C.S.S.), one of the few reliable sources of vital information about need-based financial aid.

This is one of the greatest ironies in the College Board business model, which depends on selling access to financial aid to turn a profit.

And while the College Board may promote the PSAT as a way to access need-based scholarships, the test creates its own economic barrier- even if it is public schools that are footing the bill.

Make no mistake, schools like George Mason should pay for the PSAT. The only way to ensure students receive equal access protection under the law is by, as Director of Counseling, Ilana Reyes, put it, “leveling the playing field” and paying for the test.

However, while George Mason may be able to afford the cost of administering a $16 test to nearly a thousand students, many schools are not so fortunate. And schools cannot simply choose another test.

“I’ve been in this field for 15 years and I’ve only ever experienced College Board,” said Reyes. “When I was a kid I experienced College Board. The College Board has done a fantastic job institutionalizing themselves in American educational culture.”

At George Mason, many students see College Board tests as useful, if occasionally unfair, steps towards getting into a good college.

“The [PSAT] test can be super helpful when it comes to the college application process,” said senior, Nicholas Wells.

Last year, Wells qualified for the National Merit Scholarship Program- an academic scholarship offered to students who score above a certain benchmark on the PSAT.

“I know some people who are very smart and don’t do well on it, but in my opinion, the test is pretty reliable.”

And while there is a solid argument to be made for standardized testing, the organization to provide it should be able to demonstrate a historical and current commitment to prioritizing “equity and excellence in education” over profit margins.

This, the College Board fails to do.

Colter Adams is the Lasso's Senior Political Junkie, and Managing Editor. He is also a part-time musician and a massive film buff.

Miles Jackson • Jan 7, 2019 at 4:19 PM

Lovely. Just lovely. It truly lifts my spirits to hear someone else share my anathema for the vile, insidious, and disgusting excuse of a philanthropic organization that calls itself the College Board.