What Mason students actually think about the Pledge of Allegiance

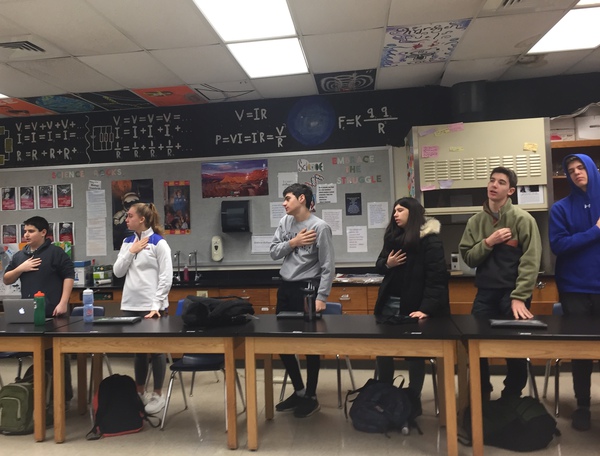

Freshman students stand for the Pledge on Friday morning. Left to right: Rani Altarazi, Anna Dickson, Joseph Burke, June Musurlian, Will Jacobson, and Josh Wattles. Photo credit to Julia Bonilla.

January 10, 2020

Every morning, Mason Students begin their day by reciting (or at least listening to) the same 31 words while they stand, holding their hands over their heart, facing a flag, which, by state law, is hung in every classroom. Then, they sit back down and go about their regular day.

Many students stand up and recite the Pledge of Allegiance without a second thought, joining the bandwagon of other students who don’t really consider why or why not they are participating, but don’t want to stand out among their peers. Others have formulated stronger beliefs surrounding the pledge.

To some, the pledge is a social activity. Sophomore Drew Miller explained that he determines his level of participation based on what the rest of the class is doing. “[I don’t participate] just because a lot of people in my classes don’t. It’s usually just the teachers,” he said.

“I just stand up [during the Pledge of Allegiance], because I’m tired in the morning,” sophomore Eduardo Kennedy said. To him, the history of the pledge of allegiance is insignificant because “It was created in, like, the 1900s.”

Many students don’t care enough to partake in the pledge, and it acts as an eye-rolling and tiring part of their daily school routine. Freshman June Musurlian said she does participate, but is reluctant to do so.

“I participate because I have no choice…I know I have a choice but at this point, I just say it because everybody else does. I say it but I don’t feel it when I say it,” she said.

Some students have more passionate opinions surrounding the Pledge of Allegiance.

Freshman Anna Tibbetts gets upset when other students fail to say the pledge.

“It means they don’t care about authority,” she said. “I don’t really care if they don’t care about authority, but if everyone else is standing up and getting out of their comfortable position to get up and put their hand on their chest, it’s really not that hard.”

On the other hand, freshman Rita Williamson hasn’t said the Pledge of Allegiance since seventh grade and intends to never recite it again.

“It’s not something I believe in and the fact that we even have to say it is kind of dystopian,” Rita said. “It doesn’t apply to America. ‘Freedom and justice for all’– not everyone in this country is free; there isn’t justice for everyone. If I ever say [the pledge] again, it’s only going to be once that line becomes applicable to America.”

Since the history of the Pledge of Allegiance is not taught in school, student participation is often based solely on habits enforced from a young age that have been carried all the way to high school, without being unpacked or legitimized, using historical knowledge.

“[I feel like] we’re just memorizing this speech and reciting it; we don’t really learn the history, I actually have no idea what it is,” freshman Sophia Koo said.

The Pledge of Allegiance was created in 1892 by Christian minister, Francis Bellamy. It was originally popularized in a children’s magazine The Youth’s Companion as an attempt to promote American nationalism in children and was eventually instilled in all public schools, along with the mandatory hanging of the American Flag.

In 1954, Congress added the phrase “under God” to the pledge, to establish separation from Communist ideology and Atheism, which were highly feared at the time. With this change, the Pledge of Allegiance became both an institutionalized expression of government obedience and a public recognition of religious influence on America.

“My understanding is that the Pledge of Allegiance was initially instituted in the Cold War, during the Red Scare when people were afraid of communist infiltration and intellectual diversity,” said Ms. Anna Barr, a World History and Geography II teacher at Mason.

Barr said formally teaching the history of the pledge would “affect participation because the pledge of allegiance is one of those things that happens in the mornings and students don’t give it a lot of thought, but when you know that context it may make you more comfortable doing it, or less comfortable doing it.”

“It’s definitely a conversation worth having and it’s a history worth knowing,” Barr said.