The SAT has long been a cornerstone of college admissions in the United States, designed to provide a standardized measure for evaluating students from diverse educational backgrounds. While some believe the test levels the playing field, I argue that it does the opposite. It perpetuates stress, anxiety, and socioeconomic disparities that make it an ineffective measure of student potential.

As spring approached during my junior year, my classmates and I prepared for the SAT in March. I, hoping to get ahead, had already taken two SATs in the fall and spent months on practice exams. The anticipation loomed over me–it felt as if this test could determine my entire future. We were under immense pressure to achieve high scores, knowing that college admissions often rely on this single exam.

It quickly became clear how important preparation was. I and many of my peers were fortunate enough to afford tutoring and test-prep resources, but others have to rely solely on free online resources. This disparity in access made it painfully obvious: the SAT does not create a level playing field. Instead, it amplifies the existing inequalities in our education system, favoring students who can afford costly preparation and multiple attempts.

When March 8 arrived, I was ready. This was my third and hopefully final attempt, my last chance to prove that my months of hard work would pay off. I entered the testing room, felt the familiar wave of anxiety, and reminded myself that I had done everything I could to prepare. I entered my testing room and sat down in my seat to feel stress fill my chest. This was normal, though. I had taken the test before, overcame this stress, and I knew the only way to achieve a higher score was if I set the worry aside. As I began the first section I was confident, I was doing okay on the reading but nothing extraordinary. Then came the math section, which could be an absolute train wreck if I got stuck too long on one question. It’s infamous for torturing students, especially those who don’t particularly enjoy math. After the first half I felt unbelievably confident, I had never understood the math so well, and then began to breeze through the harder module. I had put in the work and preparation, only to finally feel it was paying off.

And then, suddenly, my test ended.

A message popped up on my screen: “Congratulations! The test is complete, and your scores have been submitted.” But I still had 14 minutes left. I knew that I had time left, I was only halfway done. I had just checked the clock. I looked around and saw my classmates still working. My hand shot up, and so did one other student’s. The proctor was just as confused as we were. After a few minutes, we were told there was nothing to be done. We had to go home with no answers.

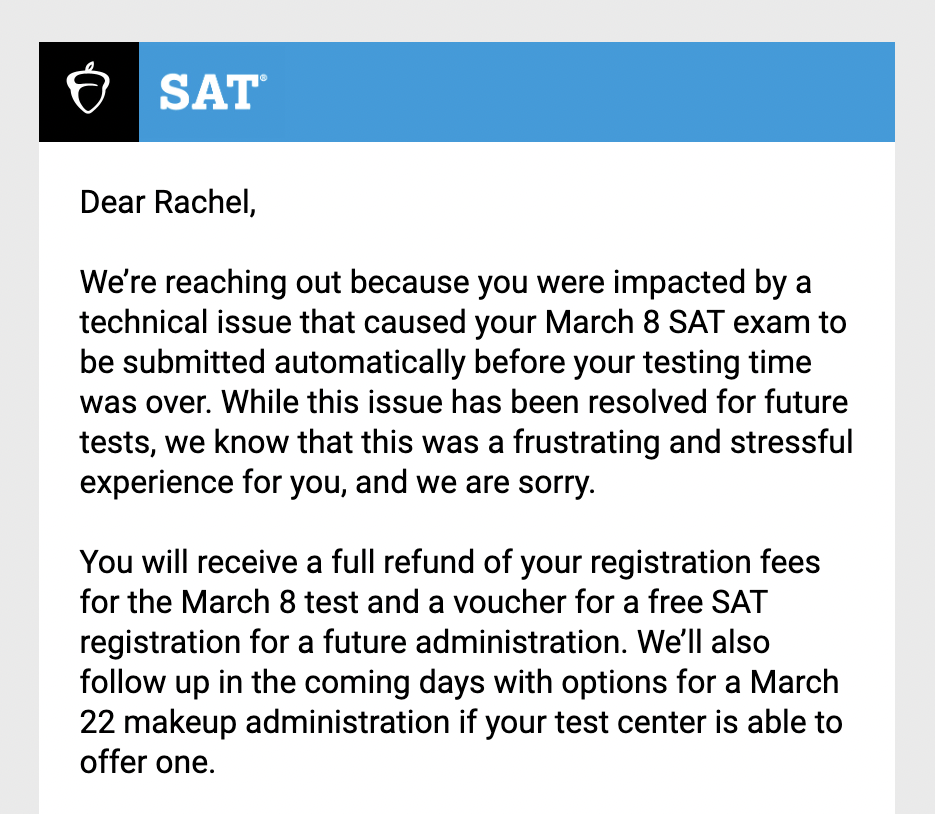

Would my scores still count? Could I retake the section I had lost? Would I have to redo the entire test? Why had this happened to only a few of us? These questions raced through my mind, adding an extra layer of stress to an already high-stakes situation. Hours later, I received an email from the College Board apologizing for the error and offering a refund along with a free retake. But no refund could erase the frustration and anxiety caused by this mistake. A single glitch had disrupted months of preparation, leaving me questioning the fairness of the entire system.

Beyond its technical flaws and stress-inducing nature, the SAT reinforces a narrow and outdated definition of intelligence. I believe that SAT scores do not correlate with one’s success. A student’s GPA, extracurricular involvement, and personal essays provide a much clearer picture of their potential than a single test score can.

Moreover, the SAT disproportionately rewards students who excel in standardized test-taking rather than those who demonstrate creativity, resilience, or problem-solving skills. It values memorization over curiosity and adaptability–qualities that are arguably far more important in higher education and beyond. A 2019 study by the University of Chicago found that high school GPA is a far stronger predictor of college success than standardized test scores, further challenging the SAT’s role as a key admissions factor.

Furthermore, a growing number of colleges and universities recognize the flaws of standardized testing and have started adopting test-optional policies. The entire University of California system no longer accepts SAT scores for admission. These schools understand that a student’s potential cannot be summed up by one number.

It is ingrained in our minds that the SAT is the golden standard of intelligence and college readiness. It’s not. It favors the wealthy, exacerbates inequality, and places unnecessary stress on students who are already juggling numerous academic and extracurricular commitments. As more schools abandon standardized testing requirements, we should question why we continue to place so much emphasis on a test that does not truly define a student’s potential.

After all of this, I, amongst my strong hatred of the SAT, will sit for another examination. Because we are all a part of a broader system, and the fact is, the only way to have influence in changing that system, is by working with it from the bottom, until your voice has the potential to be heard when you reach the top. So in my tiring spring of junior year as an IB diploma candidate juggling all of my athletics and extracurriculars, I will take the SAT and work to achieve a higher score, because that number still has some influence in defining me. And it is inevitable that, for many schools, to even have my application seen in the same category as others, I must make my number a couple of points higher.