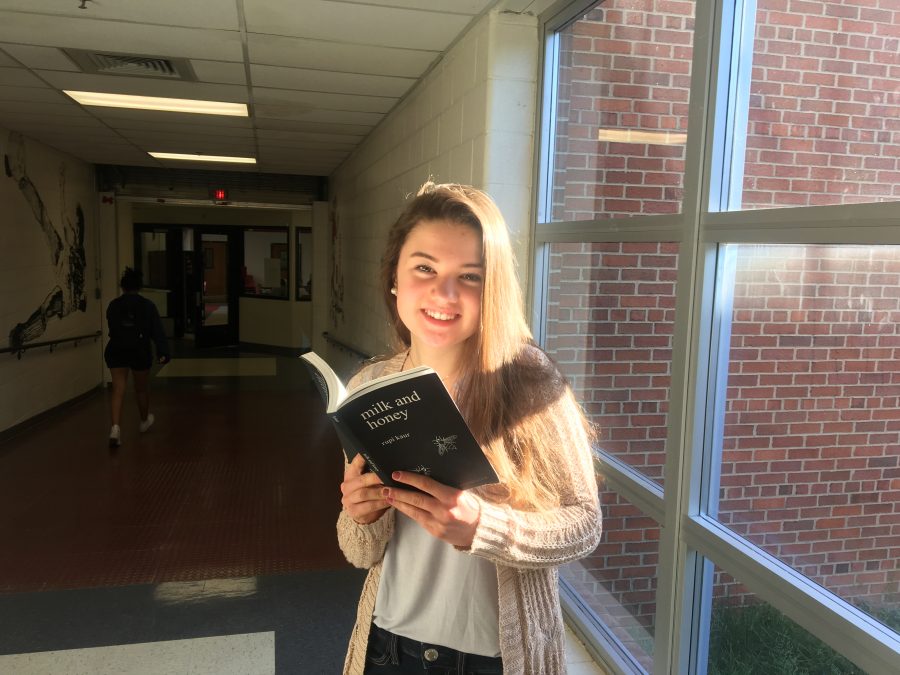

When I asked freshman Grace Tarpgaard if she had heard of poet Rupi Kaur, she lit up. “Yes! I love her, I follow her on Instagram!”

In that regard, Tarpgaard is one of 2.6 million. Those are numbers characteristic of a popstar, not a poet. And Kaur is more than internet famous–the poet’s debut collection, milk and honey, has sold millions of copies and spent 77 weeks at the top of the New York Times Paperback Fiction Bestseller List. Even now, four years since its release, milk and honey sits at second. Kaur’s most recent collection, the sun and her flowers, has shattered expectations as well, debuting at the top of countless bestseller lists in October 2017 and remaining near the top to date.

This is not normal for poets; usually, a poetry collection is lucky to sell a few thousand copies. But slowly, within the past few years, Kaur’s success has grown to be less and less of an anomaly. She is part of a new generation of poets, one of celebrity and fan bases. Dubbed Instapoets, Kaur, Lang Leav, R.M. Drake, Atticus, and dozens more write by an unspoken guideline: each poem must be able to go viral. Through brevity and direct language, Instapoetry is reaching teenagers in astounding numbers–teenagers like Tarpgaard, and dozens more at our own high school.

Why is that? What does Kaur’s poetry have to offer? And what does this mean for poetry?

“She uses this simplicity…she doesn’t need capitalization or punctuation or anything fancy, she lets the words stand on their own,” Tarpgaard explained to me. “[Her poems] don’t always have rhyme, or certain syllable counts, they just tell the story and it’s beautiful.”

This “simplicity” is best described by examples.

https://www.instagram.com/p/BfoOHhYAQTt/?hl=en&taken-by=rupikaur_

https://www.instagram.com/p/BZSH4gnggNn/?hl=en&taken-by=rupikaur_https://www.instagram.com/p/BfoOHhYAQTt/?hl=en&taken-by=rupikaur_

https://www.instagram.com/p/lQdkeqHA_v/?hl=en&taken-by=rupikaur_

Kaur’s style is distinct. Her minimalism expands beyond her punctuation and capitalization (or rather lack thereof); her poems are without subtleties, compromising complexity for understandability. A reader can fully absorb Kaur’s work scrolling through Instagram. There are no complexities that warrant careful analysis, no obscure references or overarching metaphors that leave the reader to ruminate.

It is this minimalism characteristic of Instapoetry that much of Kaur’s success can be attributed to. It doesn’t take a poet, or even a poetry fan, to understand and enjoy Kaur’s poems. Her work is, by design, accessible.

“[Instapoetry] is allowing this generation to delve into poetry…without having to make us suffer the way we have to do sometimes in school,” said freshman Gillian Murphy.

Tarpgaard had similar praise: “You don’t have to sit and puzzle for hours.”

From this emerges a common criticism, usually targeting Kaur’s audience rather than Kaur herself. Many find Instapoetry’s success emblematic of the deteriorating intellect and attention spans of younger generations.

Even Murphy has had this concern, lamenting, “In a few ways it’s kind of tragic…I don’t think anyone wants to spend the time anymore to read poetry and understand it when it’s longer than three or four sentences.”

Junior Julianna Markus, however, sees the rise of simplistic writing not as a loss but as a shift. “We’re still pursuing knowledge and we’re still learning but we’re doing it differently. Just because we’re enjoying this kind of poetry doesn’t mean that we’re not gaining knowledge from it.”

And teens are gaining insight and growing from Kaur’s work. Though her poetry may not make her readers better English students, her work deals with complicated and controversial topics–abuse, envy, and rape, to name a few. She writes about being a woman, a woman of color, and an immigrant. For many of her fans, milk and honey and the sun an her flowers are lesson books on self love and intersectional feminism.

“She’s empowering,” Tarpgaard said. “I can pick up her books and feel more confident in myself.”

Freshman Maryn Hiscott praised this aspect of Kaur’s work, too. “They’re good ideas,” she told me. But Hiscott is not a fan. “The poet in me is crying out in despair,” she exclaimed, throwing her hands in the air.

Hiscott is a poet herself, and in that sense her distaste for Kaur’s work is not a complete surprise. The poetry community is riddled with criticism of Rupi Kaur. Hiscott finds Kaur’s poetry unpolished and lacking in technical skill. “You need to learn the rules before you break the rules,” she explained, “But this feels like a blatant disregard of the rules.”

Technical praise of Kaur is not often defending her syntax, rather her aesthetic skill. Her poems are uniform, all in the same font and similar formatting, and are typically paired with delicate line drawings (hand drawn by Kaur). Markus described their effect, saying, “I think they do enhance the poem. The way they’re kind of sketchy goes with the way that her poetry isn’t polished or with a specific structure, but you can understand them.”

https://www.instagram.com/p/BY5_JKJgV96/?hl=en&taken-by=rupikaur_

Evidently, Kaur’s rise to fame, and the broader success of Instapoetry, is complicated. Thoughts on poetry’s evolution seem to come on a spectrum: on one end, those who see it as a tragic loss of depth and quality, and on the other, those who see it as a transformation allowing poetry to reach more readers and kickstart important dialogue. In reality, it’s probably a little bit of both. For better or for worse, there is no denying that Rupi Kaur and her compatriots are making their mark on the world–and they are starting with students like us.

Sue Wyckoff • May 3, 2018 at 12:05 PM

Very nice and complete article. I did not know rupi kaur’s work and I find it interesting