No, the ‘Liberal Arts’ aren’t dying

Marlboro College, a liberal arts school in southern Vermont, nearly shut down before merging with Emerson College, based in Boston. (Photo via Wikimedia Commons)

December 13, 2019

My first college fair was one of the most intimidating and claustrophobic experiences of my life.

Scores of students crowded around the tables of big state schools, grabbing for brochures and business cards. Parents pushed their kids aside to shout questions at admissions officers, or not-so-subtly mention their undergraduate experiences.

Amidst the chaos, I noticed a smiling man in a flannel shirt, with his feet up on his table. The sign read “Marlboro College.” As I began to walk apprehensively in his direction, he seemed genuinely surprised by my interest.

“You sure you’re not looking for the help desk?” asked the man, grinning.

Self-deprecating joke. Good, a real person. Still, I cringed, waiting for the tired question every college representative had asked me so far: “What’s your major?”

It never came. Instead, “If you’re not sick of school as you know it then you might want to move along. If you are though, I can tell you about Marlboro.”

In 2019, Marlboro College announced plans to shutter its facilities, amidst declining enrollment and increasing financial challenges. While the school was rescued by Emerson College, many see the closing of Marlboro – and schools like it- as reflective of a change in the viability of the liberal arts model of education.

“Marlboro is the latest small New England institution to confront the realities of demographic declines,” The Chronicle of Higher Education announced soberly.

“Liberal arts colleges struggle to make a case for themselves,” proposed the Hechinger Report, after the near-closing of Sweet Briar College in Virginia.

“The Liberal Arts Weren’t Murdered – They Committed Suicide,” smirked the conservative National Review, after the University of Wisconsin cut several liberal arts majors, and changed its motto from “the search for truth” to “meet the state’s workforce needs.”

Most of these gloom-and-doom predictions boil down to two issues. The increasing dominance of STEM, and the supposed inability of the Liberal Arts model to prepare students for it. The stereotype of the useless liberal arts degree – and the “failing” institutions that provide them – is pervasive in George Mason’s senior class.

“Oh god, not good, nothing good,” Hunter Broxson said when I asked what came to mind when he heard the term “liberal arts.”

“People who get a liberal arts degree… they don’t know what field they want to go into,” George Hoak said.

“Zero money,” Sammy Zaveri said. “I would never go there. I’m looking for a place that is strong in STEM.”

Personally, I am skeptical of STEM because it is more exclusionary in nature than a cohesive framework of study. Science, technology, engineering, and math are tangentially related and more noticeable for what they leave out – the humanities and social sciences.

Nevertheless, it is undeniable that STEM majors and jobs place students at an advantage in the workplace. There is quantitative data to suggest liberal arts majors make less money than STEM and business majors on average, and owe more in student loans.

However, is it really fair to say that a liberal arts education is less rewarding than a more conventional college experience? Furthermore, is the liberal arts model itself truly on the decline?

To begin with, it is no revelation that someone pursuing a pre-professional degree (pre-Med, pre-Law), or a degree tailored to a very specific workforce demand (engineering, computer science) will find a higher paying job, faster. However, incorporating this into the argument against the liberal arts ignores a crucial reality; it has never been the mission of the liberal arts program to serve as a fast-track to a career.

The self-fulfilling claim that the liberal arts are inadequate for the times would have been just as applicable in the 1890s, or 1950s. Afterall, hallmark programs like classical studies or anthropology were not anymore suited to the Industrial Revolution or the Nuclear Age, then they are now to the Age of the Internet.

The liberal arts curriculum is built on the assumption that higher education is more than simply an extension of workforce demand. Instead, it is an opportunity for self-examination, for breaking down boundaries, and for seeing nuance in a world that is often mistaken for black and white. In a time of unprecedented polarization, and massive ethical challenges in areas like information technology and the environment, we should be embracing these values, not belittling them.

Which brings me to my second point: in no way must choosing a major based on the job market be weighed over the liberal arts.

In an interview with the Atlantic’s Adam Harris, environmental historian, Greg Summers, who teaches at the University of Wisconsin- Stevens Point, said that employers don’t want to choose between graduates with technical ability and graduates with a liberal-arts major.

Instead, “they want both of those things.”

If anything, the liberal arts are additive. Instead of asking students to learn the fundamentals of coding and physics they challenge students to connect their abstract studies to real-world challenges. Employers and graduate schools know this and prioritize it.

The number one school for job placement in the country is Harvey Mudd College, a liberal arts school specializing in engineering.

Even for students on non-STEM tracks at liberal arts schools, there is evidence that their experience is just as fulfilling, if not quite as lucrative.

Based on 2019 data, of the top 25 schools for student satisfaction, more than half- along with the top three, Vassar, Williams, and Elon- were liberal arts colleges. Other schools that cracked the top 25 include Ivy Leagues and renowned public universities like UVA and UNC.

So is there really a looming threat to the liberal arts curricular model?

Not really.

There are certainly statistical biases that make liberal arts colleges appear more vulnerable. Most are private, meaning they cannot be rescued or subsidized by large state education budgets, and most are small, resulting in smaller total endowments and alumni support networks. Therefore, when a liberal arts school does crash, it crashes hard.

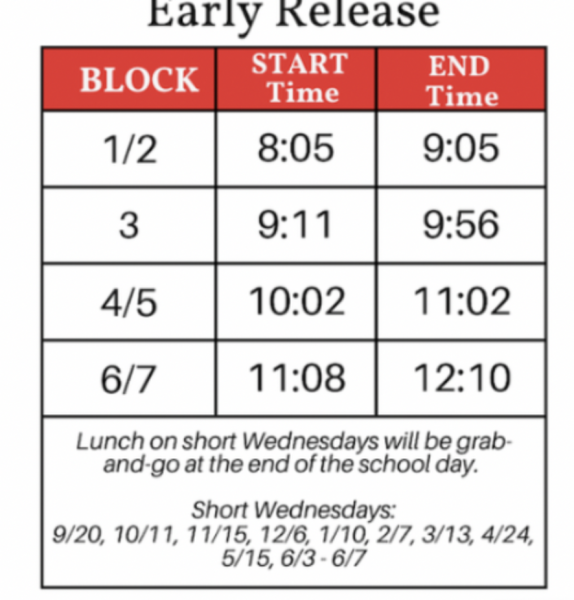

However, the top liberal arts colleges continue to report increasing applicant numbers and plentiful financial resources. If the average endowment were distributed amongst the average student body at one of the top ten liberal arts schools, each student would receive roughly 898,000 dollars. At the top ten research universities, including several Ivy League institutions, this number is closer to 466,420.

Only 9 out of the 84 colleges that have closed since 2016 maintained a “liberal arts” curriculum according to Education Dive data. This was far fewer than the number of public satellite campuses, community colleges, religious schools, and professional schools during this time frame. Of the 15, many, such as Green Mountain College and Newbury College– were highly specialized, lacking a diversified field of majors.

While the liberal arts model may face threats at the margins, so does the tertiary system as a whole. The biggest risk to America’s great experiment in education is the recurring reinforcement of stereotypes of liberal arts degrees and majors, which can dissuade ideal applicants from applying.

As reformers and advocates consider ways to adapt higher education to new challenges, they must assume that this process is more nuanced than simply mirroring workforce demand.

A fair assumption, given the last attempt to adapt an entire education system entirely to a restructuring of the economy, resulted in two monsters of inequity: common core requirements and standardized testing.